Tonight's installment deals with working oneself out of painted corners. Once in a while, I wind up realizing I've removed the part from its base too early and no longer have a way to mount it back in the lathe for one more needed operation. It can leave you scratching your head and muttering things the kiddies shouldn't hear.

That wasn't the case in this particular instance, as I chose to make the cut off early, rather than risk life and limb by working right up against the spinning chuck with a hand file. I knew I'd have to revisit the problem, but since I already had newly established indexing surfaces for the milling and drilling requirements, I took it in stride. I have Philp Duclos to thank for the solution. (I'm really beginning to like this guy)

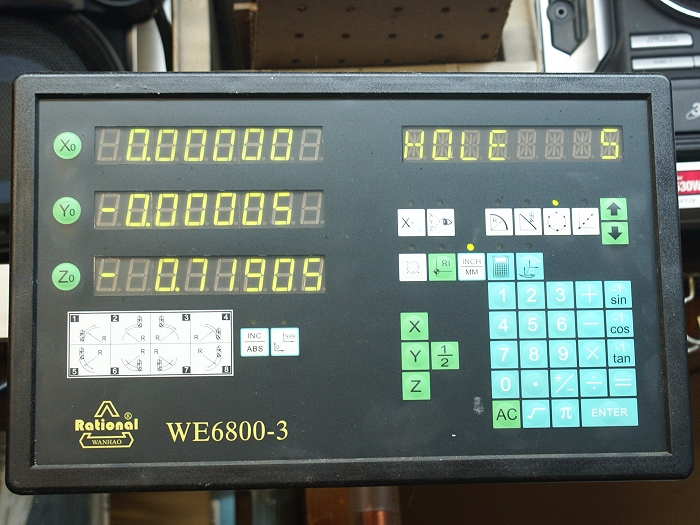

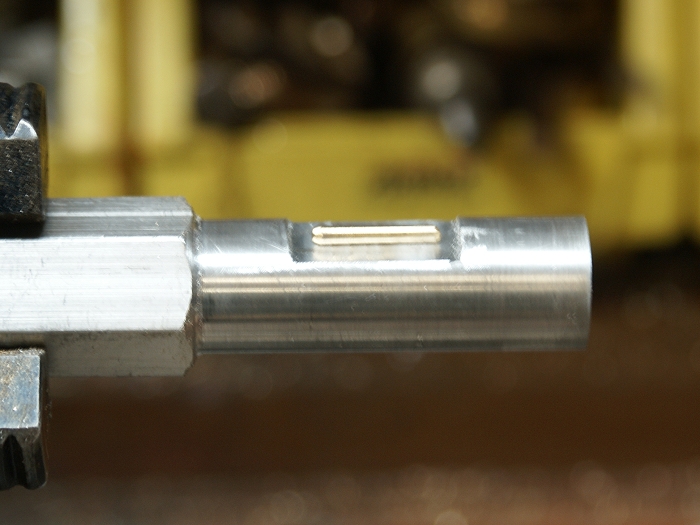

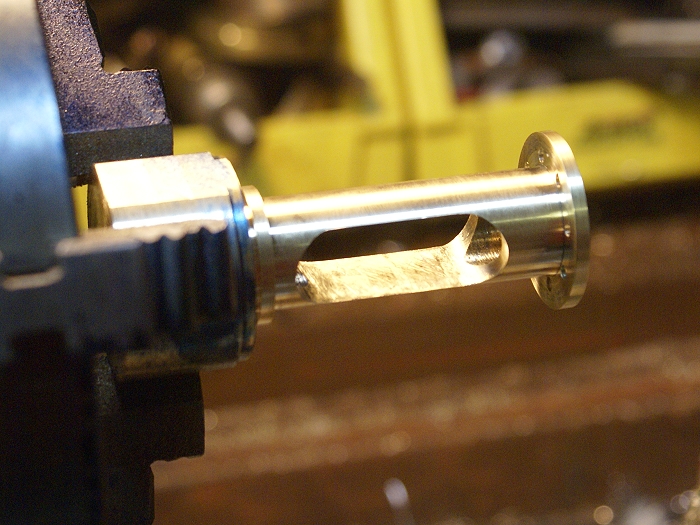

A short chapters in one of his Shop Wisdom books shared a down and dirty, easy to make, quick release mandrel that can be made on the fly, for just such situations. His tip was to turn a shaft to a close running fit, notch it with a shallow cut and place a small round dowel in the slot as a locking pin. This pin has to sit about .002 lower than the overall diameter of the shaft.

A gentle twist of the work piece in the counter (anti) clockwise direction will lock the cylinder on the shaft and hold it for turning operations, as long as you don't try to make too heavy cuts. The lathe will actually tighten the work piece as you work. When finished, a gentle twist in the clockwise direction will unlock the work piece and allow it to easily slide off the shaft.

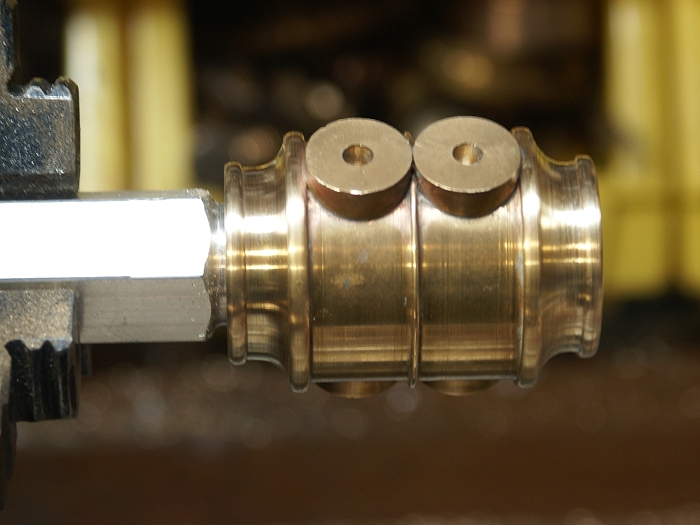

This trick allowed me to finish rounding off the bead on the cylinder end and to clean up the flange surface where I'd had to restart the cut off and missed the original cut by a few thousandths. Since this prevented the glad from seating seamlessly, it had to go. As I said before.... easy, quick and one of those down and dirty little tricks that can save your bacon.....eh?

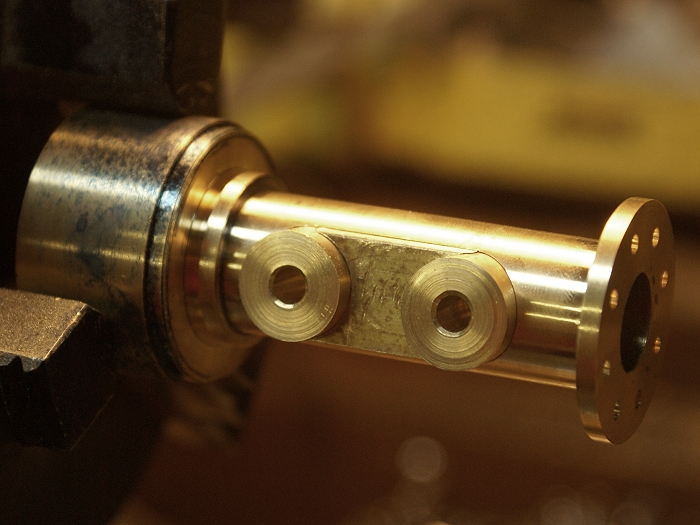

Okay.... I'll admit to miscalculations when I make them, but this one was more of a midstream design change that had to be compensated for. The spacer that goes between cylinders had to be remade after I decide to have hex heads on the gland nuts, instead of recessing them. This meant the first one was suddenly short by a full 1/4 inch. No sweat, but it did add to the number of already very plentiful holes to be drilled.

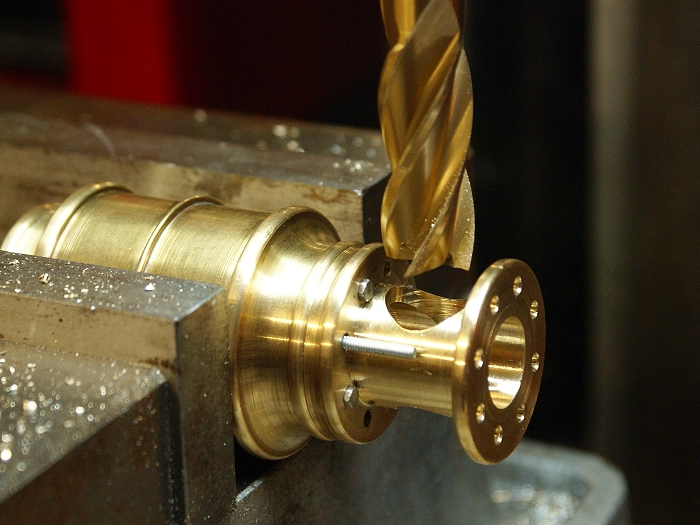

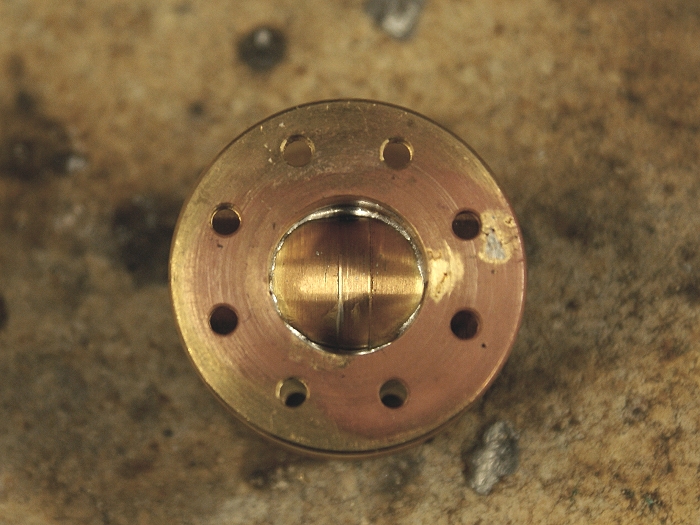

I popped the new one into the mill, drilled the first 8 holes. Since these holes are critical to alignment, I decided not to drill on through and risk the drill point wandering off on its own. So how would one flip a round part and match up the holes in the same locations as the ones on the other flange? Nope.... I couldn't leave a flat spot on this piece so another means of indexing was needed.

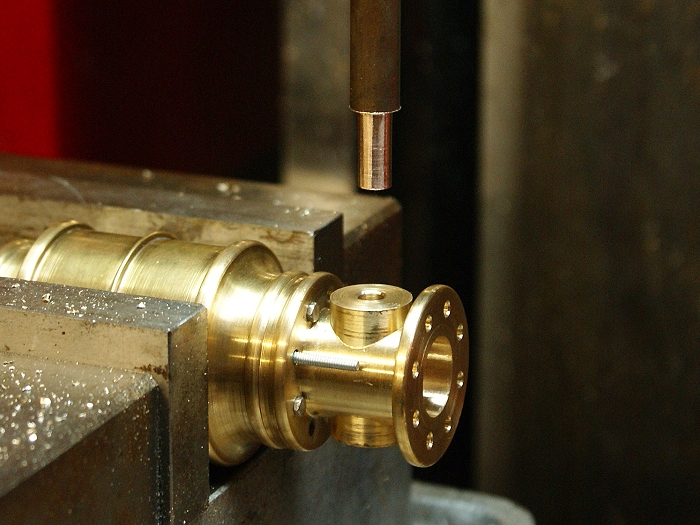

I've already turned the pistons and the piston rod was simply a piece of 3/16 drill rod, so I placed the piston in the cylinder, slid the gland in place along with the spacer. I then bolted them in place using four 2-56 hexhead screws. Before I tightened things down I moved the gland around a bit to find the point where there was least friction on the piston. (more on this in a minute). Once all was free, I tightened the bolts and put the whole assembly in the mill. The photo below shows it awaiting wiggling to center the quill before drilling the 8 holes.

As you can see, having the flat indexing points is proving to be invaluable to this project. They have made the hole placements painless if no less boring....LOL They will remain until the cylinder section is ready to bolt to the engine base, which is not that far away at this point.

I mentioned "moving the gland around" up above. Since the glands serve as the "head" for these cylinders, they are critical to the overall alignment of the pistons and piston rod. This engine will have to almost perfectly align at 6 separate points and still remain low friction if it is to run at all. Since the glands are "trapped" by the spacer assembly and the cross head guide, they were made with slightly over sized holes to allow them to "float" a few thousandths while being aligned. They will be locked into position once the other components are installed and locked down. This will take some of the sweat out of being "close" but "not quite there" as things progress.

Steve