Oldmechthings

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 10, 2008

- Messages

- 153

- Reaction score

- 12

If you are going to be a machinist, or do machine work, sooner or later you will probably need or want to make a hardened part or tool. That is certainly within the grasp of the home hobbyists.

Hardenable tool steels are readily available, usually called drill rod, although available in shapes other than round. You see it listed as air, oil, or water hardening.

Air hardening is hardened by heating to a high temperature and letting cool in still air. The disadvantage for the home machinist is that it requires a temperature controlled furnace and some method of excluding oxygen during heating.

Oil and water hardening types are hardened by the same process. Heat, quench, and temper. The water type is a little cleaner, because no smoke is generated during quenching and you do not have oil dripping all over everything.

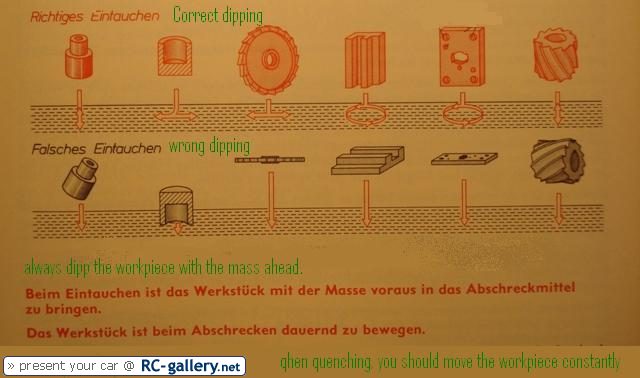

The tool steel comes from the manufacture in an an annealed state so that it can readily be machined. After you get it to the shape you want, all you have to do is harden it. You do that by heating it up just barely past the critical temperature, and quench it. What is the critical temperature? It depends on the chemical make up of the steel. Strange things happen to the molecules in the steel as they are heated, things that you do not even need to know about. All you need to know is that when it reaches the critical temperature, which by the way is a red color, the part becomes non magnetic. So as you are heating, keep touching it to a magnet and when it no longer sticks, you're there. Quench it! Now your part is as hard as it can get, in fact it is brittle hard. You would not want to use it in that condition for anything, except maybe a nozzle for your sand blaster. So now you need to draw some of the hardness out and make it a little tougher. This is done by tempering which is simply heating the part again, to some temperature between say 350 and 700 degrees, depending on the intended use of the part. The lower temperatures it would still be very hard and at the higher ones it would be like a spring. There are so many printed charts on this subject I will not attempt to cover it here. One such place is in that little spiral bound book titled "Machinist's Ready Reference". It has so much information, you ought to have a copy of it on your workbench anyway.

Shown here are some of the tools that I have made and used. there are special milling cutters, left hand taps, and the one in the fore ground is a .22 chambering reamer. The smallest tap is a #2-56 left hand. The stubby one is a 3/16" left hand Acme.

Tempering needs to be done at a controlled temperature. The old blacksmiths use to do it by watching the metal oxide colors that form at different temperatures. I use a simple little cabinet top toaster oven that is equipped with a temperature control. I double check with an oven thermometer inside. Normally I leave small parts in for about an hour, or maybe a little less.

I certainly do not know all there is to know about metallurgy, but enough to have fun with it. I hope you do too.

Birk

Hardenable tool steels are readily available, usually called drill rod, although available in shapes other than round. You see it listed as air, oil, or water hardening.

Air hardening is hardened by heating to a high temperature and letting cool in still air. The disadvantage for the home machinist is that it requires a temperature controlled furnace and some method of excluding oxygen during heating.

Oil and water hardening types are hardened by the same process. Heat, quench, and temper. The water type is a little cleaner, because no smoke is generated during quenching and you do not have oil dripping all over everything.

The tool steel comes from the manufacture in an an annealed state so that it can readily be machined. After you get it to the shape you want, all you have to do is harden it. You do that by heating it up just barely past the critical temperature, and quench it. What is the critical temperature? It depends on the chemical make up of the steel. Strange things happen to the molecules in the steel as they are heated, things that you do not even need to know about. All you need to know is that when it reaches the critical temperature, which by the way is a red color, the part becomes non magnetic. So as you are heating, keep touching it to a magnet and when it no longer sticks, you're there. Quench it! Now your part is as hard as it can get, in fact it is brittle hard. You would not want to use it in that condition for anything, except maybe a nozzle for your sand blaster. So now you need to draw some of the hardness out and make it a little tougher. This is done by tempering which is simply heating the part again, to some temperature between say 350 and 700 degrees, depending on the intended use of the part. The lower temperatures it would still be very hard and at the higher ones it would be like a spring. There are so many printed charts on this subject I will not attempt to cover it here. One such place is in that little spiral bound book titled "Machinist's Ready Reference". It has so much information, you ought to have a copy of it on your workbench anyway.

Shown here are some of the tools that I have made and used. there are special milling cutters, left hand taps, and the one in the fore ground is a .22 chambering reamer. The smallest tap is a #2-56 left hand. The stubby one is a 3/16" left hand Acme.

Tempering needs to be done at a controlled temperature. The old blacksmiths use to do it by watching the metal oxide colors that form at different temperatures. I use a simple little cabinet top toaster oven that is equipped with a temperature control. I double check with an oven thermometer inside. Normally I leave small parts in for about an hour, or maybe a little less.

I certainly do not know all there is to know about metallurgy, but enough to have fun with it. I hope you do too.

Birk