Kaleb

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 3, 2010

- Messages

- 272

- Reaction score

- 27

I've decided to borrow this idea from the watchmakers for my Frank Wiggins/Coles S.T. oscillator, so I thought I would give a bit of a walk through. I have gone on what I can glean from the web, so this may not be completely accurate, so here it goes:

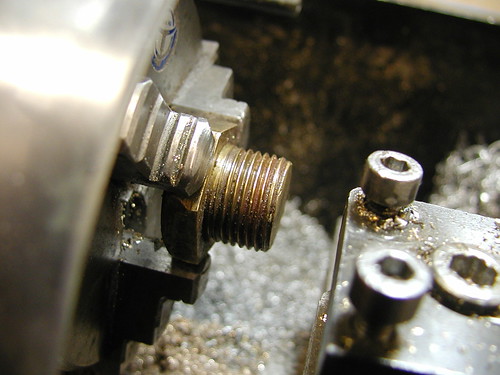

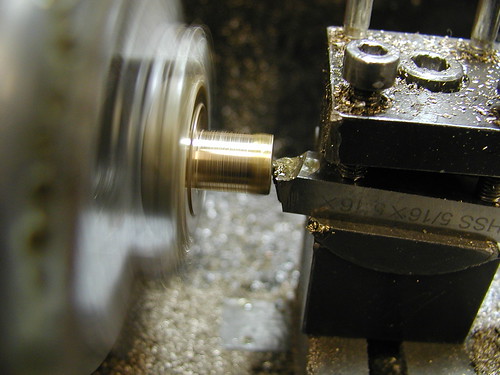

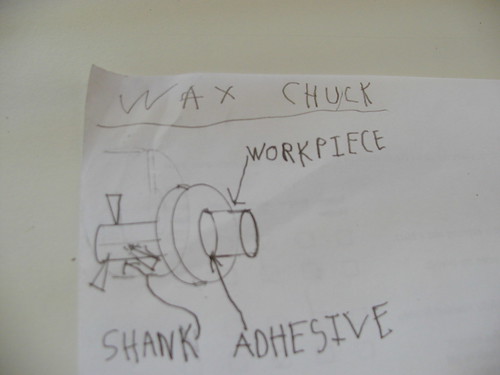

A wax chuck is a workholding fixture commonly used by clock and watchmakers for turning operations. This sketch of mine shows the basic idea:

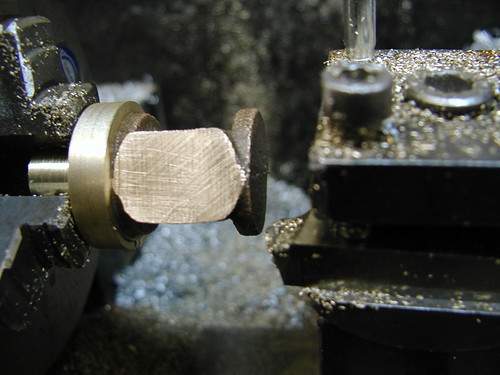

The workpiece is attached to the wax chuck by an adhesive of some description, traditionally wax, but shellac, loctite, superglue and other similar adhesives will apparently work just as well.

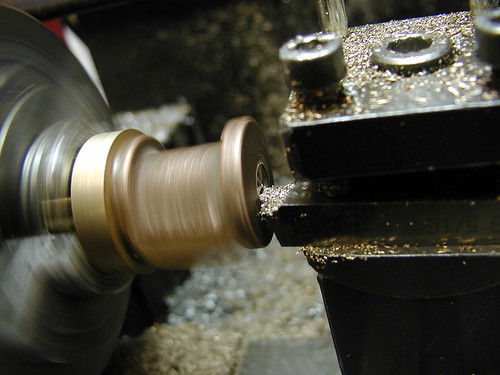

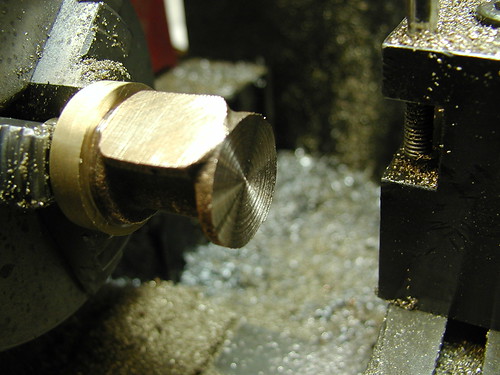

Once the adhesive has set, the wax chuck is mounted in the lathe, and machining operations take place in the usual fashion.

Once machining is complete, the workpiece is seperated from the wax chuck by heating until the adhesive either melts or breaks down.

In a watchmaker's lathe, wax chucks are usually attached to an arbor which fits directly into the headstock. They are generally made from brass, and are generally only available off the shelf for tiny watchmaker's lathes. Fortunately, it appears they would be quite simple to make. In the next post, I will walk through the process of making a wax chuck for my Sieg C1 lathe.

Here's a walk-through of using a wax chuck by a clockmaker:

http://www.snclocks.com/TechnicalInformation/Tid-Bits/Tid-Bit-2-Using-a-wax-chuck/4174805_W9qLsx#243895865_h4LDZ

A wax chuck is a workholding fixture commonly used by clock and watchmakers for turning operations. This sketch of mine shows the basic idea:

The workpiece is attached to the wax chuck by an adhesive of some description, traditionally wax, but shellac, loctite, superglue and other similar adhesives will apparently work just as well.

Once the adhesive has set, the wax chuck is mounted in the lathe, and machining operations take place in the usual fashion.

Once machining is complete, the workpiece is seperated from the wax chuck by heating until the adhesive either melts or breaks down.

In a watchmaker's lathe, wax chucks are usually attached to an arbor which fits directly into the headstock. They are generally made from brass, and are generally only available off the shelf for tiny watchmaker's lathes. Fortunately, it appears they would be quite simple to make. In the next post, I will walk through the process of making a wax chuck for my Sieg C1 lathe.

Here's a walk-through of using a wax chuck by a clockmaker:

http://www.snclocks.com/TechnicalInformation/Tid-Bits/Tid-Bit-2-Using-a-wax-chuck/4174805_W9qLsx#243895865_h4LDZ